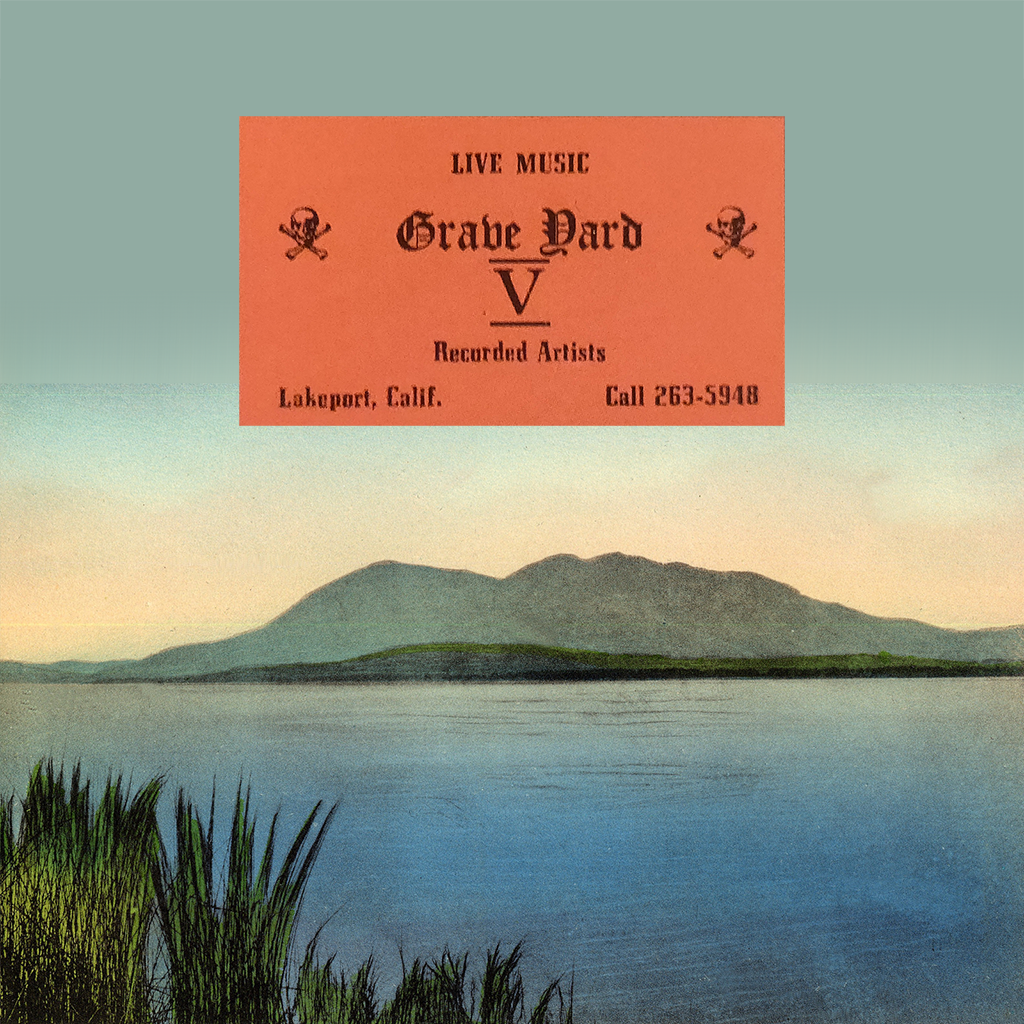

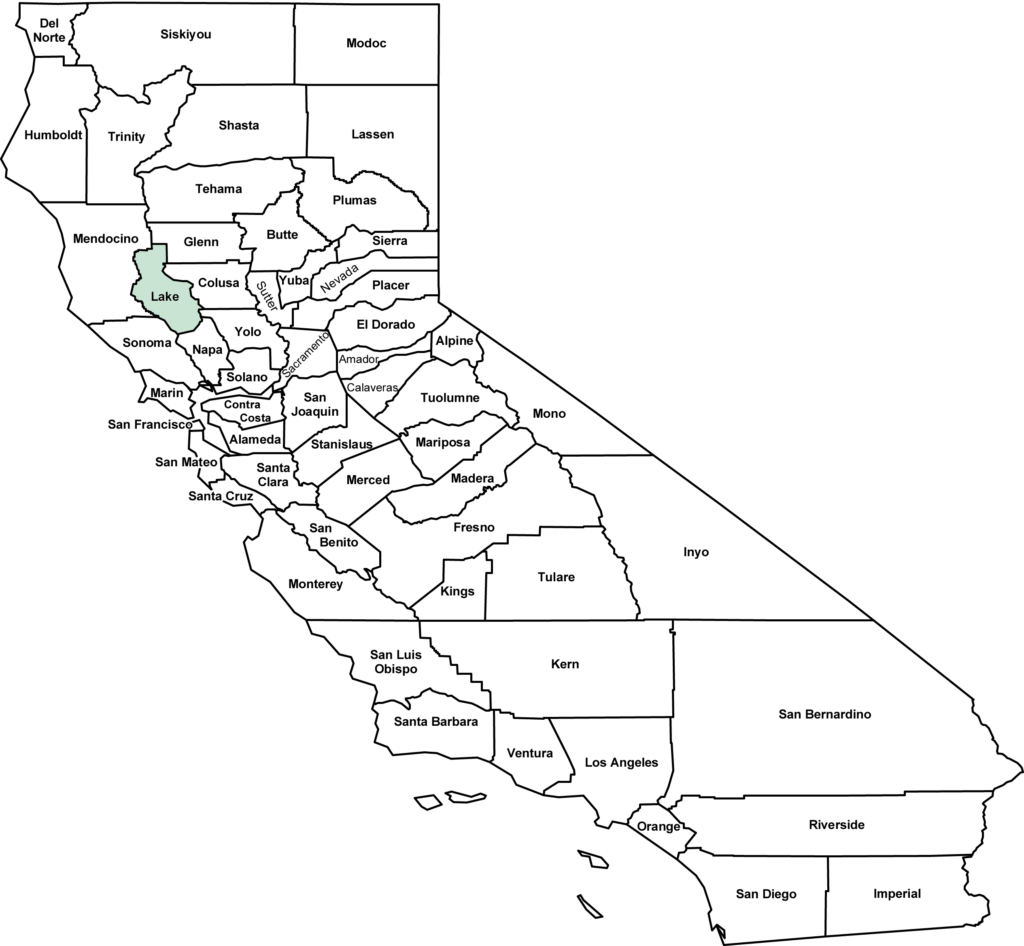

Out of the fog-laced hills and underworld shadows of Lake County emerged The Graveyard Five, a band steeped in the murk of Clear Lake’s lore, and shaped by the grit of a place well-acquainted with darkness.

Their sole 45, a fevered garage rock relic, was conceived on a dark October night in Lakeport’s Hartley Cemetery, a place where co-writers Louie Shriner and Steve Kuppinger wrestled with spirits of their own.

The B-side, “The Marble Orchard,” reads like a dirge for a night when Shriner and Kuppinger, haunted by Thunderbird wine and the sound of footsteps near the headstones, felt the unnerving howl of something feral. Louie Shriner’s lyrics evoke the scene with vivid garage punk straightforwardness. You can practically see Shriner’s trembling hands reaching for that cigarette

“We were out in the graveyard

The Graveyard Five – “The Marble Orchard”

For more than an hour

Then we heard dreadful footsteps

From behind our car

There was lightning in the sky

Someone’s going to die!

And so I said to Steve,

‘Man, hand me a cigarette.’”

The Graveyard Five’s story begins as unvarnished as Lake County itself. Local songwriters Louie Shriner and Steve Kuppinger first crossed paths one summer while working a job picking apricots. “[Louie] was sleeping in the trunk of his brother’s car,” Kuppinger recalls. “I ran into him in the restroom one day. He was trying to comb his hair and used almost a whole can of hair spray. We started talking, and one thing led to another. We both played six-string, so we made a deal to get together when we got back to Lake County. The band started that night at my house. He came over, and we played Beatles and Ventures songs, and a lot of oldies.”

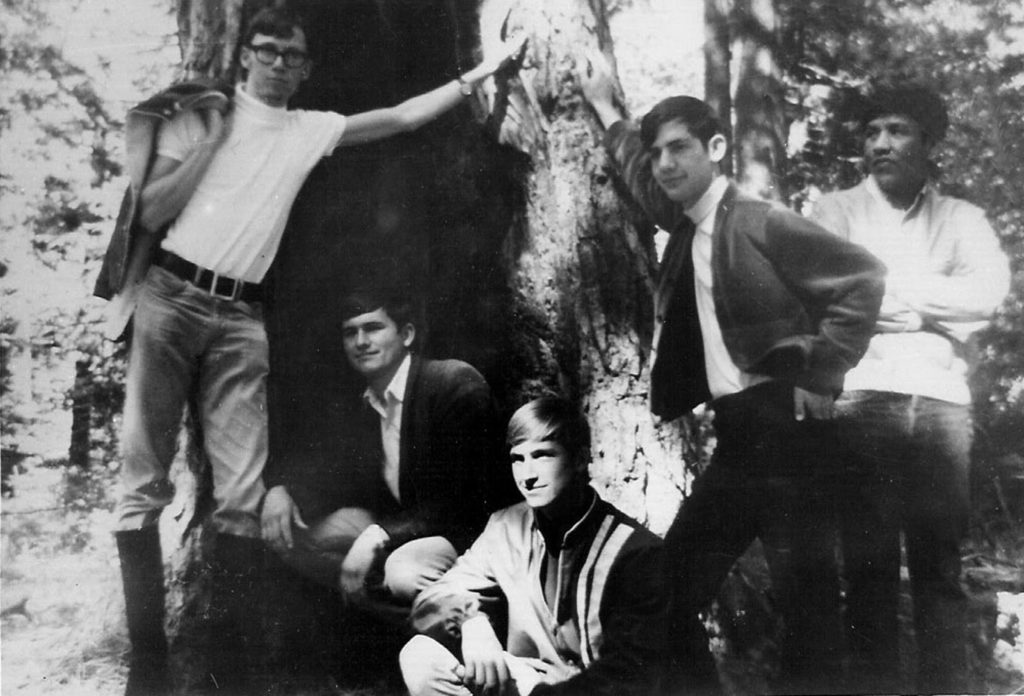

The Graveyard Five’s lineup soon solidified, with Shriner on lead guitar and vocals, Kuppinger on bass, Dave Templeton on drums, and Dennis Roller on rhythm guitar. Together, they delivered more than just noise; they created an experience steeped in the haunting theatrics of Hartley Cemetery.

Local lore surrounded their gigs, where a coffin served as the group’s eerie “fifth member.” Mid-set, a friend in face paint—or even live bats—would explode from the casket, and a band member might finish a song screaming from inside the closed lid. Lake County’s rough venues, like the Monkey Cage and various redneck bars, weren’t always prepared for their chaotic performances. “We had fights on stage, beer bottles thrown at us,” Kuppinger remembers. “It was some really hard work for very little pay.”

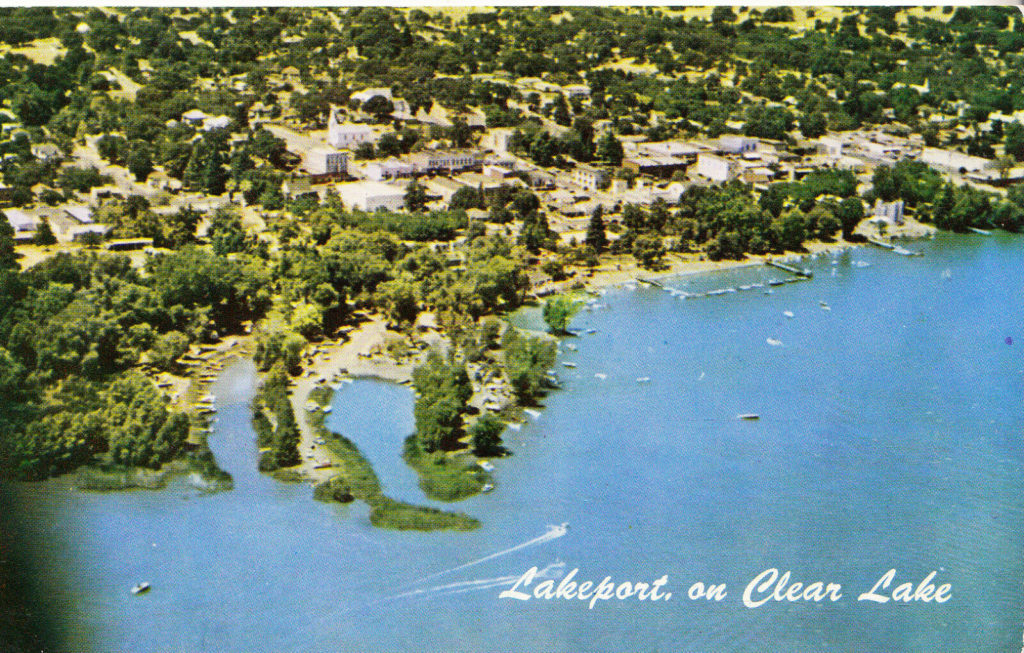

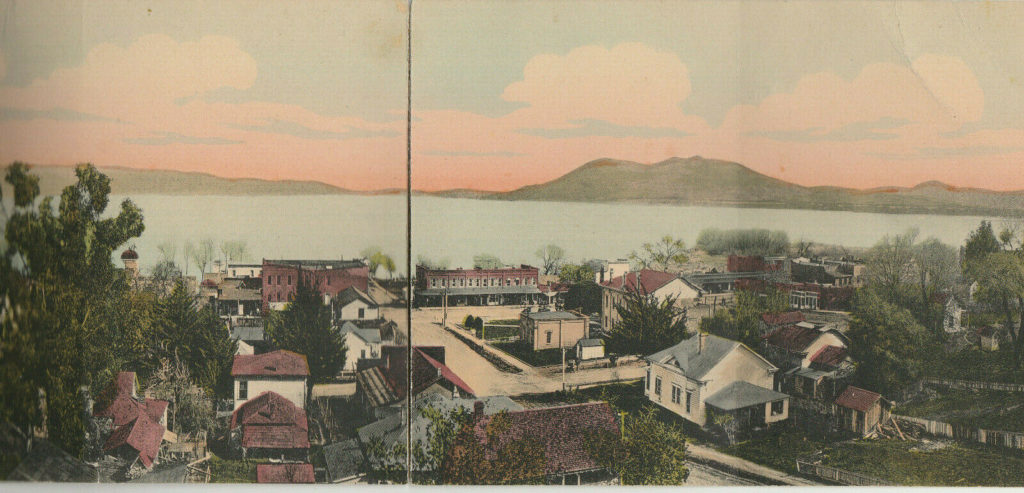

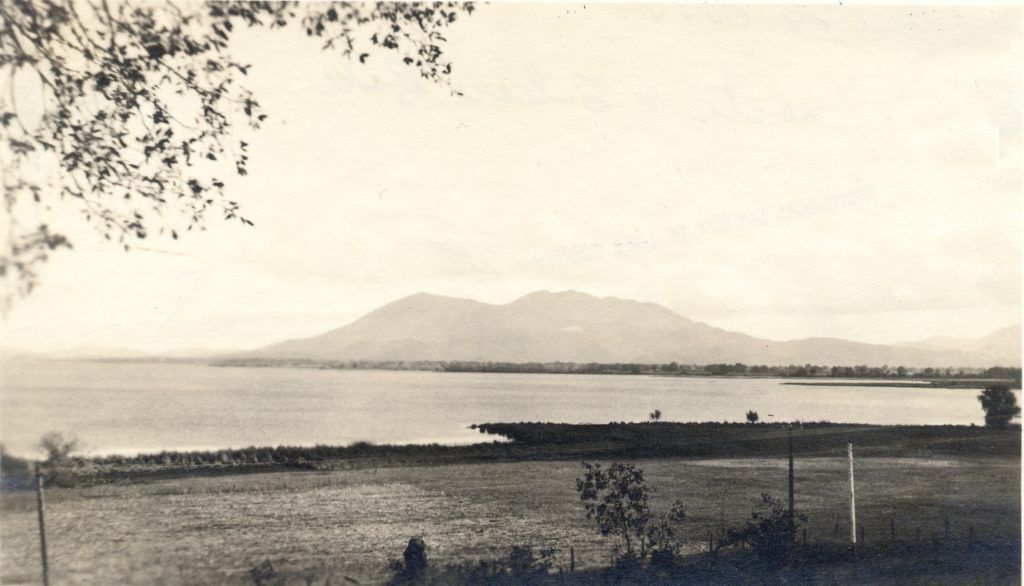

Though known to outsiders as a rustic vacation spot, locals saw Clear Lake as a place marked by grit, poverty, and ghost stories. The Graveyard Five soon became part of a small but vibrant music scene around the lake, sharing stages with other bands from nearby towns. These included The Raising Young, a Pomo Native American band from Lakeport, and March Hare from Kelseyville. Even groups from farther up the rugged northern coast, like Fort Bragg’s Dream Merchants, would occasionally come through the area.

The Graveyard Five quickly built a loyal following, especially in Redding, CA, where they headlined for a crowd of over 1,000. In a heated battle of the bands against local rivals March Hare, their raw energy won them both the night and a recording contract with Stan Sweeney’s Roseville label, Stanco. “There was almost a riot that night when we won,” Kuppinger recalls. “Everyone from Kelseyville just went to pieces, and a big fight broke out. But we got the recording contract!” The frenzy surrounding the Graveyard Five only grew, stoked by the band’s supernatural aura—a name conjured in a dark room during a Ouija board session that sent whispers and footsteps echoing outside the window.

Their A-side, “The Graveyard Theme,” is a blown-out fuzz instrumental, shredded to oblivion by a Maestro Fuzz-Tone pedal that “Light-Fingered Louie” Shriner allegedly lifted from the Jefferson Airplane at a shared Cobb Mountain gig. Their homemade light show—a jerry-rigged tire rim with spinning colored lights—added to the chaotic spectacle at Cobb.

This wasn’t the Lake County of campgrounds and lakefront charm; it was the raw, unvarnished side of a place scarred by a dark past—from the 1850s Bloody Island Massacre to today’s meth crisis, deep poverty, and relentless wildfires.

The Clear Lake area is shrouded in the supernatural. Locals in Clear Lake Oaks speak of a “pig man” seen roaming the hills of High Valley Ranch in the ’80s, while the Pomo share tales of a “donkey man” haunting the reservation and “little people” dwelling on Mount Konocti—shadowy figures darting through their homes like whispers in the night.

“It seemed that no matter where we were, it was always cold. All the girls that went with us wore coats all the time.”

Likewise, the Graveyard Five was no stranger to the otherworldly, and their mystique only grew with tales of studio hauntings. According to Kuppinger “The engineer used to curse us because he couldn’t get the place warm… the minute we got there and set up the temperature went down. He told us once that 30 minutes before we came in the place was nice and warm, but the minute we got there and set up the temperature went down. I remember being able to see my breath while I was singing back up… Then there was that growl on “Marble Orchard”. I think that whatever it was must have followed us when we left the cemetery, and I think it stayed with us everywhere we went. It seemed that no matter where we were it was always cold. All the girls that went with us wore coats all the time.”

Shriner’s increasingly erratic behavior, fueled by LSD, eventually marked the end of the Graveyard Five. He left for Florida, where, as legend has it, he threw the master tapes of their follow-up album into an alligator-infested canal. “He then threw his big extension speaker in, got on top of it, and paddled around with his guitar.”

But for Kuppinger, the haunting presence that seemed to surround the band never truly let go. “There was something very strange that followed that band, and I think it took its toll on Louis,” he reflects. “I think it has hit all of us: Dave is in prison, and, hell, Louis might even be dead by now. The last time I talked to him he was very bad off. And I haven’t gotten away clean. Thirty years ago, Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy hit me, and the doctors have been trying to control the pain ever since. There is no cure. The only one I do not know about is Dennis Roller, but he did get burned very bad — on both arms, his chest, and his back. Almost all of his little finger was burned off. So I think all of us have been hit by whatever it was that followed us around. Sometimes when it is really late and stormy, I can still feel it, almost like it is waiting out in the dark for me to start another band.”

Shriner’s ghostly presence, the electric fury of their lone 45, and the shadows of Clear Lake that seemed to follow The Graveyard Five—this is not a band you forget.

Sources:

“Up From The Grave” (Frantic Records, 2009) liner notes written by Alex Palao

Interview with Steve Kuppinger via Beyond the Beat Generation, by Mike Dugo, originally for the now defunct 60sgaragebands.com